1. What is Climate Resilience?

Currently, phenomena such as global warming, glacial melting, sea-level rise, altered precipitation patterns, and extreme weather events are becoming increasingly severe. Climate risks are particularly prominent in eight areas: low-lying coastal regions, terrestrial and marine ecosystems, critical infrastructure and networks, living standards, human health, food security, water security, and safety and population mobility[1]. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) defines resilience as the ability of a social, economic, or environmental system to handle hazardous events, trends, or disturbances, while maintaining its essential functions, identity, and structure during response or reorganization, and preserving its capacity to adapt, learn, and transform[2]. The Center for Climate and Energy Solutions (C2ES) refers to the ability to prepare for, recover from, and adapt to the adverse impacts of climate change as "climate resilience"[3].

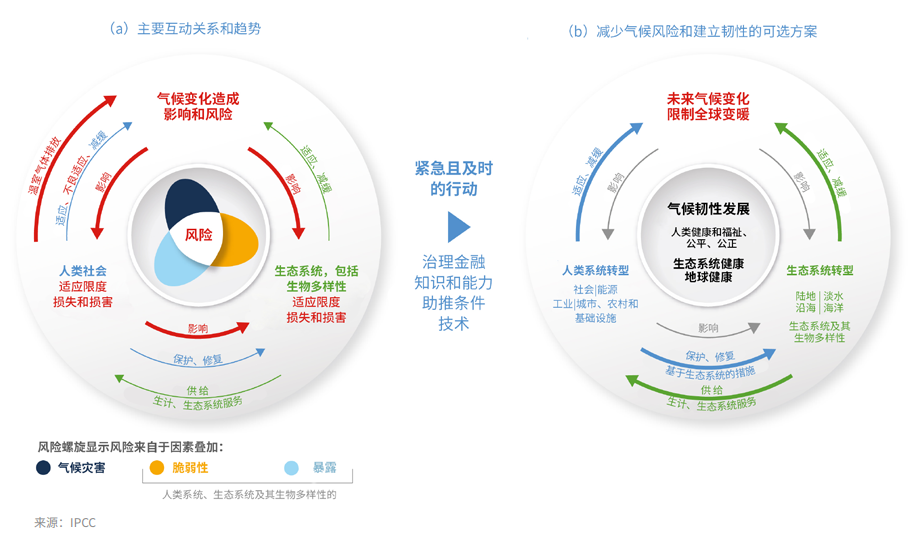

2. What is the Relationship Between Climate Resilience and Climate Change?

Climate, ecosystems, biodiversity, and human society are interdependent. Currently, the unsustainable development model of human society exacerbates climate change and damages ecosystems, while the impacts and risks posed by climate change further threaten the already stressed human economic and natural ecological systems. At the current warming level, the global average near-surface temperature in 2023 has risen by 1.45°C ± 0.12°C compared to the pre-industrial baseline (1850-1900)[4], a figure close to the 1.5°C temperature control target set by the Paris Agreement. Many regions around the world have reached the limit of adaptation, meaning that the increasing frequency of extreme weather and climate events has caused irreversible impacts in these areas. Additionally, these risks and impacts are becoming increasingly complex, compound, and cascading[1], and may interact with each other to further amplify losses and damages. For example, the melting of the Greenland Ice Sheet could trigger a critical shift in the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), reducing the transport of heat from low to high latitudes in the ocean, causing sea-level rise and heat accumulation in the Southern Ocean, and accelerating ice loss from the East Antarctic Ice Sheet[5]. Therefore, there is an urgent need for timely and robust global actions to promote comprehensive and systematic transformative adaptation and pursue a path of climate-resilient development.

Figure 1: From Climate Risks to Resilient Development[1]

3. What Impacts Will Climate Change Have on Financial Stability?

Climate change will impact the real economy, particularly key sectors such as agriculture and infrastructure.

-

Agriculture: Floods caused by extreme precipitation events damage crops and kill livestock, while frequent high temperatures and droughts reduce crop yields. The 2019 floods in Nebraska, USA, led to the drowning of a large number of livestock, resulting in economic losses of up to 440 million US dollars.

-

Infrastructure: Critical infrastructure such as housing, airports, railways, military bases, and communication systems are all threatened by extreme weather and sea-level rise, requiring large-scale repairs or replacements. In September this year, Typhoon Yagi severely hit Hainan, China, causing the collapse of wind turbines and significant losses to photovoltaic power plants, with direct economic losses in Hainan exceeding 80 billion yuan[6].

-

Health: The frequent occurrence of high temperatures and precipitation events accelerates the spread of infectious diseases and exacerbates mental health issues among the population, especially vulnerable groups, thereby reducing labor productivity and causing economic losses.

-

Tourism: Rising temperatures leading to glacial melting and excessive algal growth in water bodies adversely affect winter recreational activities and water-based tourism, hindering the development of the tourism industry and resulting in economic losses[7].

Climate risks can also be transmitted to the financial system through the real economy, affecting financial stability. Direct economic losses and asset devaluation caused by extreme weather and environmental events[8] may spread to the financial sector through insurance balance sheet channels, bank financing channels, and real economy and market liquidity channels. For example, in terms of bank financing channels: climate-related risks can lead to the devaluation of collateral due to physical damage; in addition, excessively high insurance premiums before disasters and insufficient insurance compensation after disasters can also cause collateral devaluation, deteriorate the balance sheets of households and enterprises, increase the risk of bank loan defaults, and affect bank credit supply and financial system stability[9].

Affected by policy changes, shifts in consumer preferences, and disruptive business model innovations, traditional industries may face shocks such as rising costs and industrial substitution. Financial institutions' asset allocation in traditional industries may face the risk of asset stranding[9]. Specifically, there are channels such as asset revaluation, unordered policy rhythms and low credibility. For example, in the asset revaluation channel: climate change promotes low-carbon transition, leading to a large number of high-carbon assets (such as fossil energy reserves) becoming stranded assets with sharply reduced values, causing huge losses to asset owners and increasing risks for investors and creditors. If stranded assets are written off from corporate balance sheets, it will affect the financing capacity of relevant enterprises, leading to higher financing costs, lower market value, and reduced credit ratings. Currently, large financial institutions such as BlackRock are considering reducing investments in fossil fuels; large-scale capital outflows will increase financing costs in this sector, suppress the valuation of related enterprises (such as falling stock prices), and disrupt financial markets[9].

4. What are the Main Differences Between the Concepts of Resilient Cities and Climate-Adaptive Cities?

There is an overlap between the concepts of resilient cities and climate-adaptive cities. The concept of resilient cities is relatively broad: building a resilient city is a comprehensive initiative involving multiple areas such as urban leadership and strategy, economy and society, infrastructure and ecosystems, and human health and well-being. Its fundamental purpose is to enhance a city's ability to resist, adapt to, and recover from various shock risks[10]. Urban resilience includes not only climate resilience but also economic resilience, social development resilience, and overall urban competitiveness. Climate adaptation is an important dimension of resilient cities, while climate-adaptive cities focus more on addressing the specific challenges of climate change. Building a climate-adaptive city means effectively responding to hazardous weather such as heavy rainfall, smog, droughts, sandstorms, and cold waves through urban planning, construction, and management, ensuring the normal operation of urban systems, the safety of residents' lives and property, and the stability and reliability of ecosystems[11]. Specifically, the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report points out that urban climate adaptation actions can be implemented through:

-

Improving urban infrastructure construction, including social infrastructure such as health systems, natural infrastructure such as protected natural areas, and engineering infrastructure such as information and communication technologies;

-

Incorporating climate risks and adaptation considerations into urban planning;

-

Proactively taking actions around core areas such as institutional reform, fund raising, assessment framework construction, and development transformation;

-

Adopting comprehensive measures to fully consider and safeguard the principles of fairness and justice in urban climate adaptation planning, thereby enhancing cities' ability to adapt to climate change and recover from disasters, and mitigating the adverse impacts of climate change[1].

China has a large population, complex climatic conditions, and an overall fragile ecological environment. It is also in a stage of rapid industrialization and urbanization. Climate change has already had a significant impact on urban construction and development. Therefore, current research on resilient cities in China mainly focuses on improving urban climate adaptation capacity. In 2017, the National Development and Reform Commission and the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development jointly issued a notice on pilot work for building climate-adaptive cities. The main tasks in the plan include: requiring pilot cities to strengthen the concept of urban adaptation, promote integrated construction, and incorporate climate change adaptation into urban planning and target systems; improving monitoring and early warning capabilities, and strengthening information construction and big data application; carrying out key adaptation actions, optimizing infrastructure layout, developing green buildings, constructing flood control and drainage systems, and forming a diversified management system; establishing policy test bases to encourage innovation and cooperation; and building an international cooperation platform to promote international exchanges and cooperation[12]. These requirements aim to accumulate pilot experience in building climate-adaptive cities in China to promote national sustainable development.

5. International and Domestic Experiences in Climate Resilience

San Francisco, USA

Faced with the threats and potential losses posed by sea-level rise, the City of San Francisco has formulated adaptation measures at two levels: government management-related strategies and technology-related means. Specific actions include revising zoning plans, improving existing building design standards, constructing more green infrastructure, raising building foundations, and strengthening seawall construction. In addition, San Francisco has adopted a supervision mechanism: various departments have collaborated to establish a storm event tracking and response system, continuously monitoring key indicators such as flood scope, path, and inundation depth, and summarizing experiences and lessons to improve work. Meanwhile, San Francisco's action plan proposes a variety of financing mechanisms, including cost-sharing, innovative insurance, public-interest negotiations, and specific taxes and fees, and has explored new financing methods such as resilience bonds, resilience construction service companies, and resilience impact bonds. In addressing the challenge of sea-level rise, multiple regional cooperations have been carried out among stakeholders in San Francisco, including public policy supervision and governance agencies, landowners in coastal flood-prone areas, and actively participating members of the public, which have played an important role. In the process of addressing climate change, San Francisco has accumulated valuable experiences in systematic planning, scientific assessment, data-driven decision-making, and cross-departmental coordination, which are also of great reference significance for other countries and regions[13].

Rotterdam, the Netherlands

Faced with water-related threats such as seawater intrusion and rainwater flooding, the City of Rotterdam has adopted urban adaptation strategies and built a "sponge city" in accordance with the environmental planning blueprint of the "Rotterdam Climate Initiative". First, Rotterdam has increased water storage areas through polders to store water during the rainy season for irrigation in the dry season. Second, the Dutch government has invested in the "Room for the River" project, which has transformed river courses to form a resilient buffer system with "retention, storage, and drainage" functions. In addition, Rotterdam has developed urban water spaces, using large-scale water storage devices and drainage designs to channel rainwater into urban public spaces, thereby saving funds required for the construction of traditional rainwater drainage systems. Finally, to effectively utilize water resources, Rotterdam has actively promoted green roofs: the municipal government first set targets for green roof construction area, provided subsidies based on the actual area of green roofs, and levied sewage taxes according to rainfall discharge. These measures in Rotterdam have significantly enhanced the city's ability to defend against meteorological disasters and promoted urban sustainable development[14].

Beijing, China

In recent years, the rainfall characteristics in Beijing have undergone significant changes, with frequent short-duration heavy rainfall events, increasing the disaster-causing potential of urban rainstorms. To address this, Beijing has formulated an overall flood control and drainage layout of "storing in the west, draining in the east, and diverting floods in the north and south", and launched a number of response measures, including the renovation of rainwater pumping stations, the management of small and medium-sized rivers, the Xijiao Rainwater Regulation and Storage Project, and the urban flood disaster early warning and emergency management system, to improve urban flood control and drainage capacity. In the process of urban governance, the construction costs of flood control and drainage projects in Beijing are fully borne by the municipal finance, while the maintenance costs are shared by the municipal finance and local government finance. In addition, Beijing adopts government procurement of services for facility maintenance, with costs varying according to rainfall and subject to the supervision of third-party audits. Thanks to the improvement of Beijing's flood disaster response capacity, although the heavy rainfall in 2016 exceeded the record-breaking heavy rain in 2012, the resulting disaster losses were relatively smaller, and the impact on the economy and society was significantly weakened. Drawing on Beijing's experience, other cities should coordinate from an overall perspective when responding to flood disasters, integrate the forces of multiple departments, formulate detailed plans, and adopt personalized response measures. At the same time, other cities can rely on scientific and technological means to enhance the planning, early warning, and dispatch command capabilities of urban flood control[15]

Xixian New Area, China

Located between the built-up areas of Xi'an and Xianyang, Xixian New Area covers 23 towns and sub-districts in 7 counties (districts) under the jurisdiction of the two cities. Over the past 50 years, Xixian New Area has faced climate change challenges such as rising temperatures, significant phased changes in precipitation, and an increase in extreme weather events, which have posed threats to urban development, infrastructure stability, drainage system efficiency, and public safety. To address this, Xixian New Area has taken a series of measures to enhance the city's climate adaptation capacity, including three directions: conducting climate vulnerability assessments, formulating and implementing policies related to climate change adaptation, and promoting climate change adaptation actions in a coordinated manner. It has strived to build a modern pastoral ecological city and constructed rooftop gardens with a total area exceeding 5,000 square meters. In addition, Xixian New Area has innovated climate investment and financing channels, investing in the new area's construction through both equity and debt; the new area has strengthened organizational leadership, established expert teams, and expanded channels for the participation of various market entities to ensure the comprehensive coordination of project construction progress. By building a comprehensive construction plan and a localized standard system, and relying on innovative design and technological support, Xixian New Area has achieved goals such as flood control and drainage, and ecological greening, formed a replicable construction model and experience, and encouraged each new city to formulate key actions for urban climate change adaptation based on its own advantages[16].

References

[1] Beijing Green Innovation and Development Center. Climate Risks, Impacts and Resilience: Strategies, Local Actions and Investment and Financing. 2023. briefing-climate-adaptation-webinars-cn-23nov (ghub.org.cn)

[2] IPCC, 2012: Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation. A Special Report of Working Groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Field, C.B., V. Barros, T.F. Stocker, D. Qin, D.J. Dokken, K.L. Ebi, M.D. Mastrandrea, K.J. Mach, G.-K. Plattner, S.K. Allen, M. Tignor, and P.M. Midgley (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, and New York, NY, USA, 582 pp

[3] Center For Climate And Energy Solutions. What is Climate Resilience, and Why Does it Matter? 2019. what-is-climate-resilience.pdf (c2es.org)

[4] IPCC, 2023: Sections. In: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, pp. 35-115, doi: 10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647

[5] Armour, K., Marshall, J., Scott, J. et al. Southern Ocean warming delayed by circumpolar upwelling and equatorward transport. Nature Geosci 9, 549–554 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2731

[6] Yicai. Official statistics from Hainan show that "Yagi" caused losses of 80 billion yuan, far exceeding "Rammasun" 10 years ago. 2024. https://www.yicai.com/news/102268757.html

[7] Columbia Climate School. How Climate Change Impacts the Economy. 2019. https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2019/06/20/climate-change-economy-impacts/

[8] NGFS. Overview of Environmental Risk Analysis by Financial Institutions. 2020. https://www.ngfs.net/sites/default/files/media/2020/09/23/overview_of_environmental_risk_analysis_by_financial_institutions.pdf

[9] Research Bureau of the People's Bank of China. Climate-Related Financial Risks: An Analysis Based on Central Bank Functions[J]. Working Paper of the People's Bank of China, 2020(3), 1-24.

[10] ARUP. City Resilience Index. 2019. file:///D:/Downloads/city-resilience-index.pdf

[11] Fu L, Yang X, Zhang D, et al. Assessment of climate-resilient city pilots in China[J]. Chinese Journal of Urban and Environmental Studies, 2021, 9(01): 2150005.

[12] National Development and Reform Commission of the People's Republic of China. Notice on Issuing the Pilot Work Plan for Building Climate-Adaptive Cities (Fa Gai Qi Hou〔2017〕No. 343). 2017. https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xxgk/zcfb/tz/201702/t20170224_962916.html

[13] China Climate Risk and Adaptation Cooperation Project. Action Plan for Adapting to Sea-Level Rise – Case Study from San Francisco. 2020. https://climatecooperation.cn/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/San-Francisco.pdf

[14] China Climate Risk and Adaptation Cooperation Project. Rotterdam, the Netherlands: Enhancing Urban Water Resilience. 2020. https://climatecooperation.cn/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Rotterdam.pdf

[15] China Climate Risk and Adaptation Cooperation Project. Beijing: Urban Flood Disaster Response under Climate Change. 2020. https://climatecooperation.cn/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/CN-Beijing.pdf

[16] China Climate Risk and Adaptation Cooperation Project. Xixian New Area: Building a Modern Pastoral City Adapted to Climate Change. 2020. https://climatecooperation.cn/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Xixian.pdf